The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks

Igort, 2016

Reviewed by Valerie Cervantes, A23 (BFA)

Igor Truveri, who works under the pen name Igort, is one of the most prominent graphic novelists of Italy, with a career spanning a range of narrative mediums including, but not limited to, comic books, novels, essays, music, and movies. He has never limited himself to a single creative pursuit and is well known in several subsections of the art world at large. For the purposes of this review, I will focus on his work in the world of book arts. In 1980, his first professionally published comics were released in the Italian magazine Linus. Quickly thereafter, in 1981 and 1982, he would go on to publish his own magazine known as Il Penguno Guadalupa, as well as form the avant-gardist artist group known as Valvoline. The Valvoline group was a crucial element in the world of international comics as they came to redefine then-contemporary narrative techniques. Together they worked to deliver narratives that abstracted our understanding of text and other visual signifiers, activating the senses beyond sight. In more recent history, Igort founded the pre-eminent comic book publishing house of Italy known as Coconino Press, named after George Herriman’s portrayal of Coconino County, Arizona in Krazy Kat. It was through this press that Igort originally published the notebooks as two separate publications, the Quaderni Ucraini and Quaderni Russi in 2010 and 2011 respectively. The version depicted to the left was published in 2016 in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War which began officially in 2014, bringing these two works in conversation with contemporary world events.

The Ukrainian Notebooks illustrates the history of the 1932 Holodomor, a state sanctioned famine that transpired under the rule of Stalin and is reported to have taken the lives of anywhere from 1.8 to 12 million ethnic Ukrainians. In turn, The Russian Notebooks follows the life and subsequent assassination of Russian journalist and human-rights activist Anna Politkoyska, who was well-known for her denunciation of the Second Chechen War and her vehement efforts to expose acts of extreme violence and cruelty. Over the course of two years of living in Ukraine and Russia, Igort collected oral testimonies from witnesses and survivors of life under Soviet rule, as well as accounts from those close to Politkoyska to illustrate these histories faithfully. It is of note here that Igort does not choose one single voice or method of narration to relate these stories to the reader. While the conceptual framework of the piece is to present a firsthand account of the war through those that were individually affected, the narrative also dips into moments of journalism and personal memoir. The narrative voice of each passage changes along with the method that Igort used to collect the story.

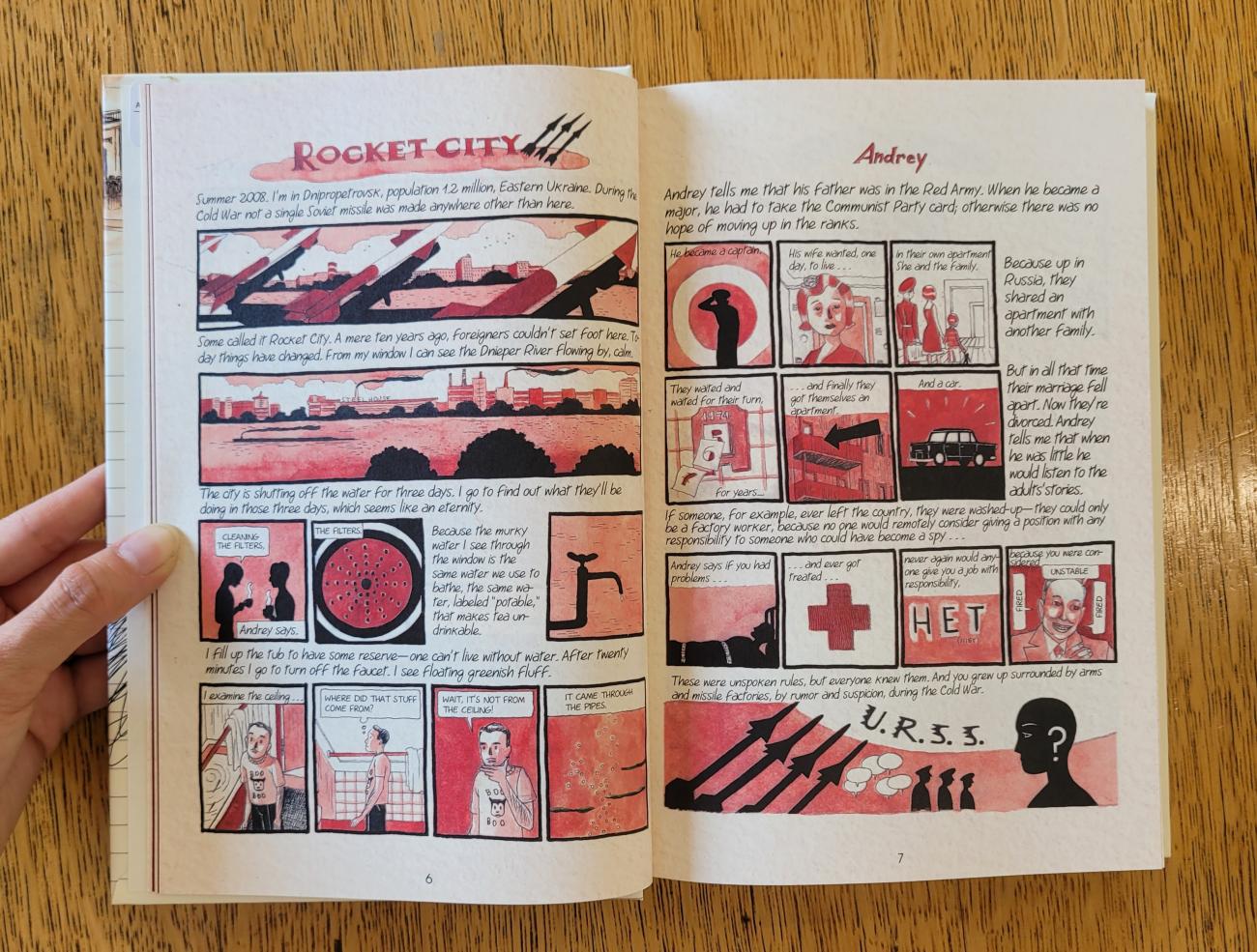

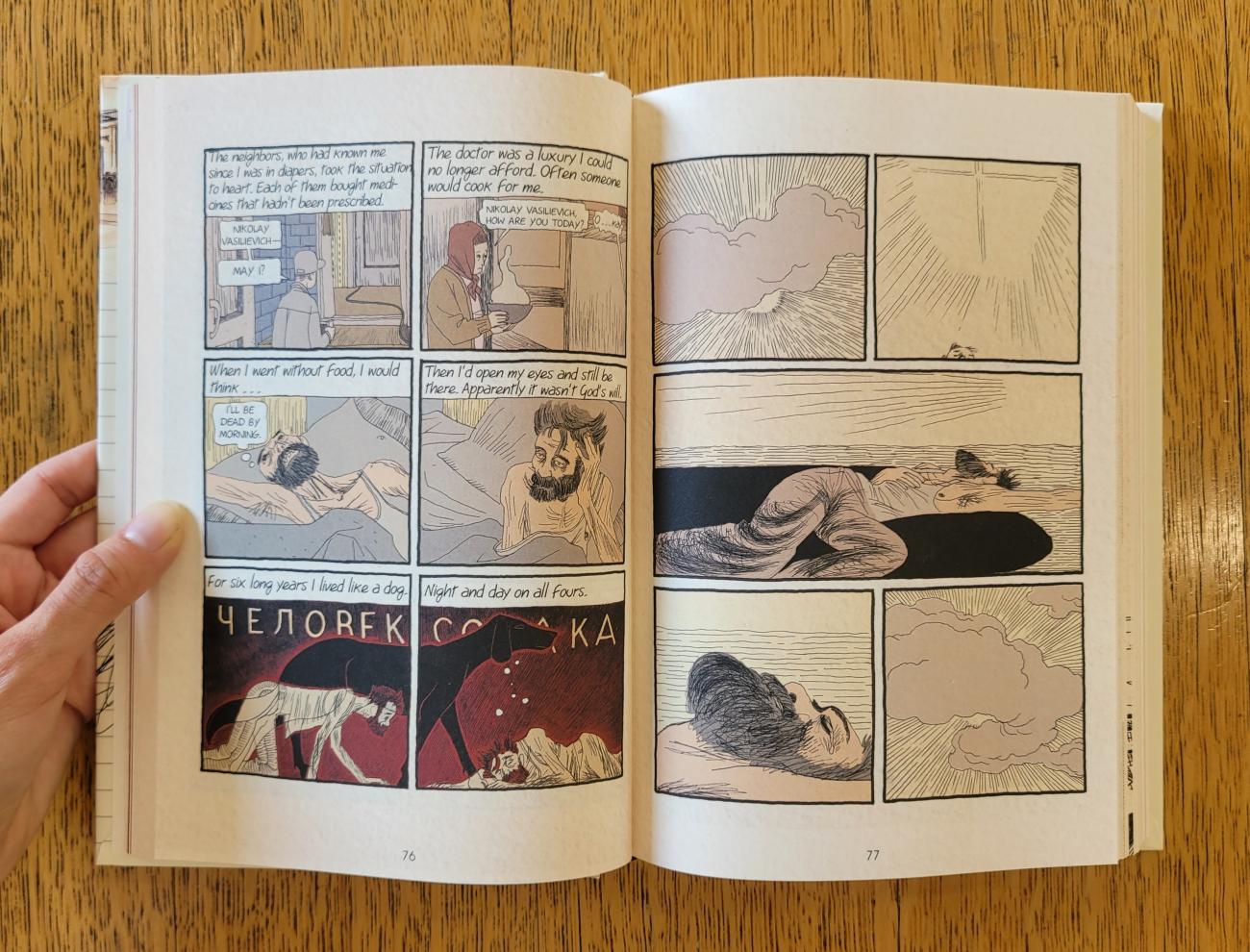

Take for instance the passages depicted in the following two spreads.

The first depicts Igort himself living in Dnipropetrovsk in the summer of 2008. It was at this time that Igort’s journey and subsequent project began. In it we get a quick lens into the living conditions and concerns of the everyday person living in then-contemporary Eastern Ukraine. The second depicts the first-hand account of one, Nikolay Vasilievich, who had lost his ability to walk after an act of abject violence and remained in the care of neighbors for several years. The text of each individual account is written as if through the eyes of the very person who experienced it. The typography of the text is relatively passive, save for some small moments here and there where the author chooses to hand-letter titles, names, and dates (e.g. Rocket City). It is of note that the typography of the narrative text throughout the novel remains minimal and unobtrusive, allowing the power of each account to speak for itself. It is perhaps one of the only constants throughout the novel, as drawing style, color palette, and layout formats change.

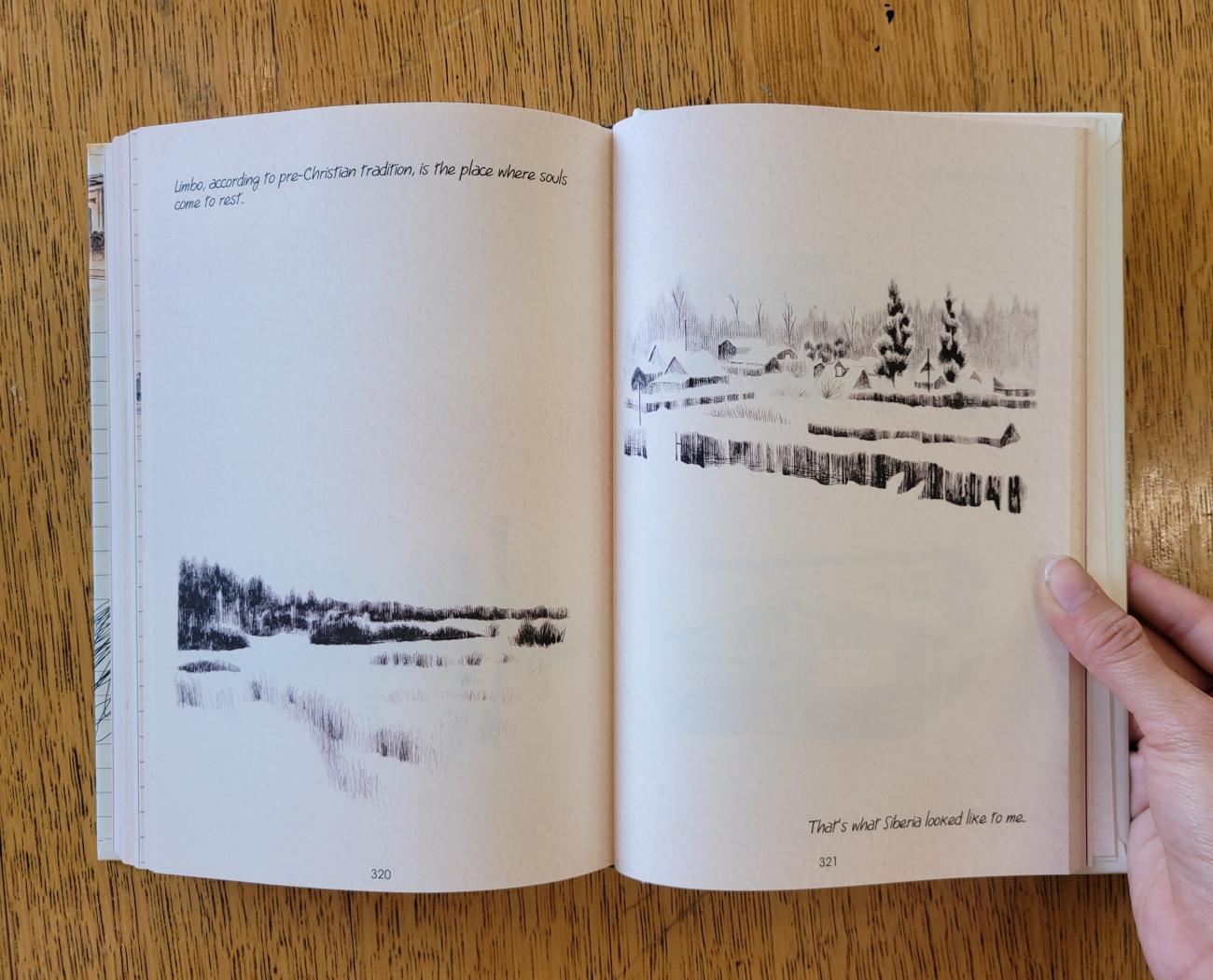

There is a wide range of drawing styles throughout the book. At times they are simple and sketchy in a small range of muted colors, other times the images are black and white — the heart-rending content not requiring any color to bolster it. One of the most striking moments of visual and sequential juxtaposition comes at the end of the novel when Igort chooses to depict Siberia through a short series of delicate black and white line drawings. The text here is delicate and unassuming, describing the pre-Christian conception of Limbo or “the place where souls come to rest.” Unlike the rest of the novel, where each passage depicts some moment of great physical and emotional turmoil, here the landscape is peaceful, quiet even. It is a moment of pause and rest for the reader. As the novel comes to a close, we come back to this great expanse of white, a lone figure falling and picking themselves back up as they cross the page. The book ends on a delicate note of hope for the future of the people living in this region.

The cover of the book is incredibly powerful. The lined paper background depicted here is used repeatedly throughout the book, reminding us of the original object which must have housed these stories as the author traveled throughout the region. The large, bold hand lettered text stands out starkly against the off-white paper background. The long soldier, gun-in-hand frames the bottom left corner of the text, leading our eyes to the subtitle Life and Death under Soviet Rule, giving us a small glimpse into the book’s contents. The design here is understated, simple, yet captivating and effective in imparting the understanding that this book will contain a written and visual portrait of life in the region. The cover certainly sells.

Another component of the marketability of this object is its high production value. While it does not contain any particularly inventive bells and whistles that some of the other artists’ books maintain, the paper, printing, and binding make for a high-quality final production. This, of course, is something that can be expected from one of the pre-eminent publishing houses in the United States, Simon and Schuster, especially given their well-regarded author. The success of the book comes down to its powerful and emotional portrayal of the human cost of the war. Each account, along with the supporting drawings, tells us of another facet of the war. The book feels full of honest vulnerability as it helps to raise awareness of an ongoing conflict and the people affected by it today. It has given me a greater appreciation for the power of graphic novels as a medium for documentary storytelling.

Related book in the library collection

5 is the perfect number

Igort, 2003